转载: Hashing in Action Understanding bcrypt

The bcrypt hashing function allows us to build a password security platform that scales with computation power and always hashes every password with a salt.

In previous posts to this Authentication Saga, we learned that storing passwords in plaintext must never be an option. Instead, we want to provide a one-way road to security by hashing passwords. However, we also explored that hashing alone is not sufficient to mitigate more involved attacks such as rainbow tables. A better way to store passwords is to add a salt to the hashing process: adding additional random data to the input of a hashing function that makes each password hash unique. The ideal authentication platform would integrate these two processes, hashing and salting, seamlessly.

There are plenty of cryptographic functions to choose from such as the SHA2 family and the SHA-3 family. However, one design problem with the SHA families is that they were designed to be computationally fast. How fast a cryptographic function can calculate a hash has an immediate and significant bearing on how safe the password is.

Faster calculations mean faster brute-force attacks, for example. Modern hardware in the form of CPUs and GPUs could compute millions, or even billions, of SHA-256 hashes per second against a stolen database. Instead of a fast function, we need a function that is slow at hashing passwords to bring attackers almost to a halt. We also want this function to be adaptive so that we can compensate for future faster hardware by being able to make the function run slower and slower over time.

At Auth0, the integrity and security of our data are one of our highest priorities. We use the industry-grade and battle-tested bcrypt algorithm to securely hash and salt passwords. bcrypt allows building a password security platform that can evolve alongside hardware technology to guard against the threats that the future may bring, such as attackers having the computing power to crack passwords twice as fast. Let’s learn about the design and specifications that make bcrypt a cryptographic security standard.

Technology changes fast. Increasing the speed and power of computers can benefit both the engineers trying to build software systems and the attackers trying to exploit them. Some cryptographic software is not designed to scale with computing power. As explained earlier, the safety of the password depends on how fast the selected cryptographic hashing function can calculate the password hash. A fast function would execute faster when running in much more powerful hardware.

To mitigate this attack vector, we could create a cryptographic hash function that can be tuned to run slower in newly available hardware; that is, the function scales with computing power. This is particularly important since, through this attack vector, people tend to keep the length of the passwords constant. Hence, in the design of a cryptographic solution for this problem, we must account for rapidly evolving hardware and constant password length.

This attack vector was well understood by cryptographers in the 90s and an algorithm by the name of bcrypt that met these design specifications was presented in 1999 at USENIX. Let’s learn how bcrypt allows us to create strong password storage systems.

bcrypt was designed by Niels Provos and David Mazières based on the Blowfish cipher: b for Blowfish and crypt for the name of the hashing function used by the UNIX password system.

crypt is a great example of failure to adapt to technology changes. According to USENIX, in 1976, crypt could hash fewer than 4 passwords per second. Since attackers need to find the pre-image of a hash in order to invert it, this made the UNIX Team feel very comfortable about the strength of crypt . However, 20 years later, a fast computer with optimized software and hardware was capable of hashing 200,000 passwords per second using that function!

Inherently, an attacker could then carry out a complete dictionary attack with extreme efficiency. Thus, cryptography that was exponentially more difficult to break as hardware became faster was required in order to hinder the speed benefits that attackers could get from hardware.

The Blowfish cipher is a fast block cipher except when changing keys, the parameters that establish the functional output of a cryptographic algorithm: each new key requires the pre-processing equivalent to encrypting about 4 kilobytes of text, which is considered very slow compared to other block ciphers. This slow key changing is beneficial to password hashing methods such as bcrypt since the extra computational demand helps protect against dictionary and brute force attacks by slowing down the attack.

As shown in “Blowfish in practice”, bcrypt is able to mitigate those kinds of attacks by combining the expensive key setup phase of Blowfish with a variable number of iterations to increase the workload and duration of hash calculations. The largest benefit of bcrypt is that, over time, the iteration count can be increased to make it slower allowing bcrypt to scale with computing power. We can dimish any benefits attackers may get from faster hardware by increasing the number of iterations to make bcrypt slower.

Another benefit of bcrypt is that it requires a salt by default. Let’s take a deeper look at how this hashing function works!

Provos and Mazières, the designers of bcrypt , used the expensive key setup phase of the Blowfish cipher to develop a new key setup algorithm for Blowfish named “eksblowfish”, which stands for “expensive key schedule Blowfish.”

What’s “key setup”? According to Ian Howson, a software engineer at NVIDIA: “Most ciphers consist of a key setup phase and an operation phase. During key setup, the internal state is initialised. During operation, input ciphertext or plaintext is encrypted or decrypted. Key setup only needs to be conducted once for each key that is used”

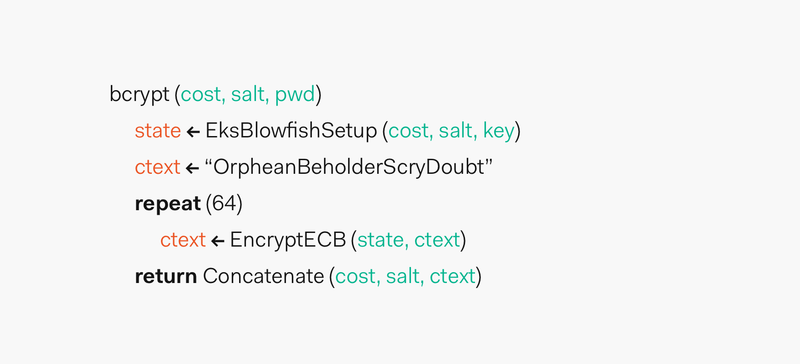

bcryptruns in two phases:

Phase 1:

A function called EksBlowfishSetup is setup using the desired cost, the salt, and the password to initialize the state of eksblowfish . Then, bcrypt spends a lot of time running an expensive key schedule which consists of performing a key derivation where we derive a set of subkeys from a primary key. Here, the password is used as the primary key. In case that the user selected a bad or short password, we stretch that password/key into a longer password/key. The aforementioned practice is also known as key stretching.

What we are going through this first phase is to promote key strengthening to slow down calculations which in turn also slow down attackers.

Phase 2:

The magic value is the 192-bit value OrpheanBeholderScryDoubt . This value is encrypted 64 times using eksblowfish in ECB mode with the state from the previous phase. The output of this phase is the cost and the 128-bit salt value concatenated with the result of the encryption loop.

The resulting hash is prefixed with $2a$ , $2y$ , or $2b$ . The prefixes are added to indicate usage of bcrypt and its version.

The result of bcrypt achieves core properties of a secure password function as defined by its designers:

- It’s preimage resistant.

- The salt space is large enough to mitigate precomputation attacks, such as rainbow tables.

- It has an adaptable cost.

The designers of bcrypt believe that the function will hold its strength and value for many years. Its mathematical design gives assurance to cryptographers about its resilience to attacks.

Regarding adaptable cost, we could say that bcrypt is an adaptive hash function as we are able to increase the number of iterations performed by the function based on a passed key factor, the cost. This adaptability is what allows us to compensate for increasing computer power, but it comes with an opportunity cost: speed or security?

The challenge of security engineers is to decide what cost to set for the function. This cost is also known as the work factor. OWASP recommends as a common rule of thumb for work factor setting to tune the cost so that the function runs as slow as possible without affecting the users’ experience and without increasing the need to use additional hardware that may be over budget.

Let’s take a closer look at an example based on OWASP recommendations:

- Perform UX research to find what are acceptable user wait times for registration and authentication.

- If the accepted wait time is 1 second, tune the cost of

bcryptfor it to run in 1 second on your hardware. - Analyze with your security team if the computation time is enough to mitigate and slow down attacks.

Users may be fine waiting for 1 or 2 seconds as they don’t have to consistently authenticate. The process could still be perceived as quick. Whereas, this delay would frustrate the efforts of an attacker to quickly compute a rainbow table.

Being able to tune the cost of bcrypt allow us to scale with hardware optimization. Following a modern definition of Moore’s Law, the number of transistors per square inch on integrated systems has been doubling approximately every 18 months. In 2 years, we could increase the cost factor to accommodate any change. However, we need to be careful with this: if we simply increase the work factor of bcrypt in our code, everyone will be locked out. A migration process is necessary in this case.

Check out a cool graph that shows the numbers of transistors on integrated circuit chips from 1971 to 2016.

As an example on how the increasing the work factor increases the work time, I created a Node.js script that computed the hash of DFGh5546*%^__90 using a cost from 10 to 20.

1 | const bcrypt = require("bcrypt"); |

In the next section, we are going to explore the Node.js implementation in more detail. The script was run on a 2017 MacBook Pro with the following specs (We get nice equipment at Auth0! Join us!):

- Processor: 2.8 GHz Intel Core i7

- Memory: 16 GB 2133 MHz LPDDR3

- Graphics: Radeon Pro 555 2048 MB, Intel HD Graphics 630 1536 MB

These are the results:

1 | bcrypt | cost: 10, time to hash: 65.683ms |

Plotting this data in Wolfram Alpha to create a least-squares fit graph, we observe that the time to hash a password grows exponentially as the cost is increased in this particular hardware configuration:

For this data set, Wolfram Alpha gives us the following least-squares best fit equation:

1 | 28.3722 e^(0.705681x) |

If we wanted to predict how long would it take to hash a password in this system when the cost is 30 , we could simply plug that value for x :

1 | 28.3722 e^(0.705681(30)) = 44370461014.7 |

A cost factor of 30 could take 44370461014.7 milliseconds to calculate. That is, 739507.68 minutes or 513.55 days! A much faster machine optimized with the latest and the greatest technology available today could have smaller computation times. However, bcrypt can easily scale our hashing process to accommodate to faster hardware, leaving us a lot of wiggle room to prevent attackers from benefiting from future technology improvements.

If a company ever detects or suspects that a data breach has compromised passwords, even in hash form, it must prompt its users to change their password right away. While hashing and salting prevent a brute-force attack of billions of attempts to be successful, a single password crack is computationally feasible. An attacker may, with tremendous amount of computational power, or by sheer luck, crack a single password, but even then, the process would be most certainly slow due to the characteristics of bcrypt , giving the company and their users precious time to change passwords.

Now that we understand how bcrypt works, let’s explore how it can be implemented in a web application at a high level.

We are going to explore its implementation using Node.js and its popular node.bcrypt.js implementation. You don’t need to create a Node.js project. The purpose of this section is to show the common steps that developers have to take when integrating bcrypt in their backend.

node.bcrypt.js is installed via npm , a Node.js package manager via the following command:

1 | npm install bcrypt |

Then, on an entry-point file for the server, such as app.js , we create a set of variables to refer throughout the implementation:

1 | // app.js |

bcrypt gives us access to a Node.js library that has utility methods to facilitate the hashing process. saltRounds represent the cost or work factor. We are going to use a random password, plainTextPassword1 , for the example.

This Node.js implementation is interesting because it gives us two different techniques to hash the passwords. Let’s explore them.

1 | // app.js |

Using the Promise pattern to control the asynchronous nature of JavaScript, in this technique, we first create a salt through the bcrypt.genSalt function that takes the cost, saltRounds . Upon success, we get a salt value that we then pass to bcrypt.hash along with the password, plainTextPassword1 , that we want to hash. The success of bcrypt.hash provides us with the hash that we need to store in our database. In a full implementation, we would also want to store a username along with the hash in this final step.

Notice that I included some console.log statements to show the values of the salt and the hash as the process went along. Something that is really helpful in this implementation is that you do not have to create the salt yourself. The library creates a strong salt for you.

In the first run, I got the following results in the command line:

1 | Salt: $2b$10$//DXiVVE59p7G5k/4Klx/e |

You won’t be able to 转载 these results again since the salt is completely random every time genSalt is run. Running it again, I got the following output:

1 | Salt: $2b$10$3euPcmQFCiblsZeEu5s7p. |

Hence, each password that we hash is going to have a unique salt and a unique hash. As we learned before, this helps us mitigate greatly rainbow table attacks.

In this version, we use a single function to both create the salt and hash the password:

1 | // app.js |

This technique has a smaller footprint and may be easier to test. Again, a new hash is created each time the function is run, regardless of the password being the same.

Notice how in both techniques we are storing the hash and not the password. The user’s password itself should not be stored anywhere in plaintext.

Once we have our password hashes stored in the database, how do we validate a user login? Let’s check that out.

Using the bcrypt.hash method, let’s see how we can compare a provided password with a stored hash. Since we are not connecting to a database in this example, we are going to create the hash and save it somewhere, like a text editor. The hash I got is:

$2b$10$69SrwAoAUNC5F.gtLEvrNON6VQ5EX89vNqLEqU655Oy9PeT/HRM/a .

Next, we are going to check the passwords and see how they match. First, we check if our stored hash matches the hash of the provided password:

1 | // app.js |

In this case, res is true , indicating that the password provided, when hashed, matched the stored hash.

Opposite, we expect to get false for res if we check the hash against plainTextPassword2 :

1 | // app.js |

And, effectively, res is false. We did not store the salt though, so how does bcrypt.compare know which salt to use? Looking at a previous hash/salt result, notice how the hash is the salt with the hash appended to it:

1 | Salt: $2b$10$3euPcmQFCiblsZeEu5s7p. |

bcrypt.compare deduces the salt from the hash and is able to then hash the provided password correctly for comparison.

That’s the flow of using bcrypt in Node.js. This example is very trivial and there are a lot of others things to care about such as storing username, ensuring the whole backend application is secure, doing security tests to find vulnerabilities. Hashing a password, though essential, is just a small part of a sound security strategy.

Other languages would follow a similar workflow:

- Here’s an example using Spring Security for Java.

- This example uses Django for Python.

- Finally, this example uses Laravel for PHP.

The main idea of password verification is to compare two hashes and determine if they match each other. The process is very complex. A solid identity strategy demands an organization to keep current with cryptographic advances, design a process to phase out deprecated or vulnerable algorithms, provide pen testing, invest in physical and network security among many others. With all factors considered, it isn’t easy or inexpensive.

You can minimize the overhead of hashing, salting and password management through Auth0. We solve the most complex identity use cases with an extensible and easy to integrate platform that secures billions of logins every month.

Auth0 helps you prevent critical identity data from falling into the wrong hands. We never store passwords in cleartext. Passwords are always hashed and salted using bcrypt. We’ve built state-of-the-art security into our product, to protect your business and your users.

Make the internet safer, sign up for a free Auth0 account today.